An international research group including Professor Fukun Liu at The Department of Astronomy and The Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics of Peking University in Beijing, China, presents important new results on the active galaxy OJ 287, based on the most dense and longest radio-to-high-energy observations to date. The scientists were able to test crucial binary model predictions using multiple observing tools, including the Effelsberg radio telescope and the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory. The team measured an independent mass of the black hole mass and the mass in the disk that surrounds the black hole.

The results show that an exceptionally massive black hole exceeding 10 billion solar masses is no longer needed. Instead, the results favor models with a smaller mass of 100 million solar masses for the primary black hole, consistent with the results obtained about twenty year ago by Fukun Liu and Xue-Bing Wu, also at Peking University. Several outstanding mysteries, including the apparent absence of the latest big outburst of OJ 287 (which has now been identified) and the much-discussed emission mechanism during the main outbursts, can be solved this way. Independent results on blazar physics that trace processes near the jet launching region were obtained.

These findings have strong implications for the theoretical modeling of supermassive black hole binary systems and their evolution, for understanding the physics of accretion and jet launching near supermassive black holes, for future pulsar timing vs space-based gravitational wave detection from this system, and a direct spatial resolution of this system with the Event Horizon Telescope or the future SKA.

The findings are presented in two papers published in MNRAS Letters and the Astrophysical Journal.

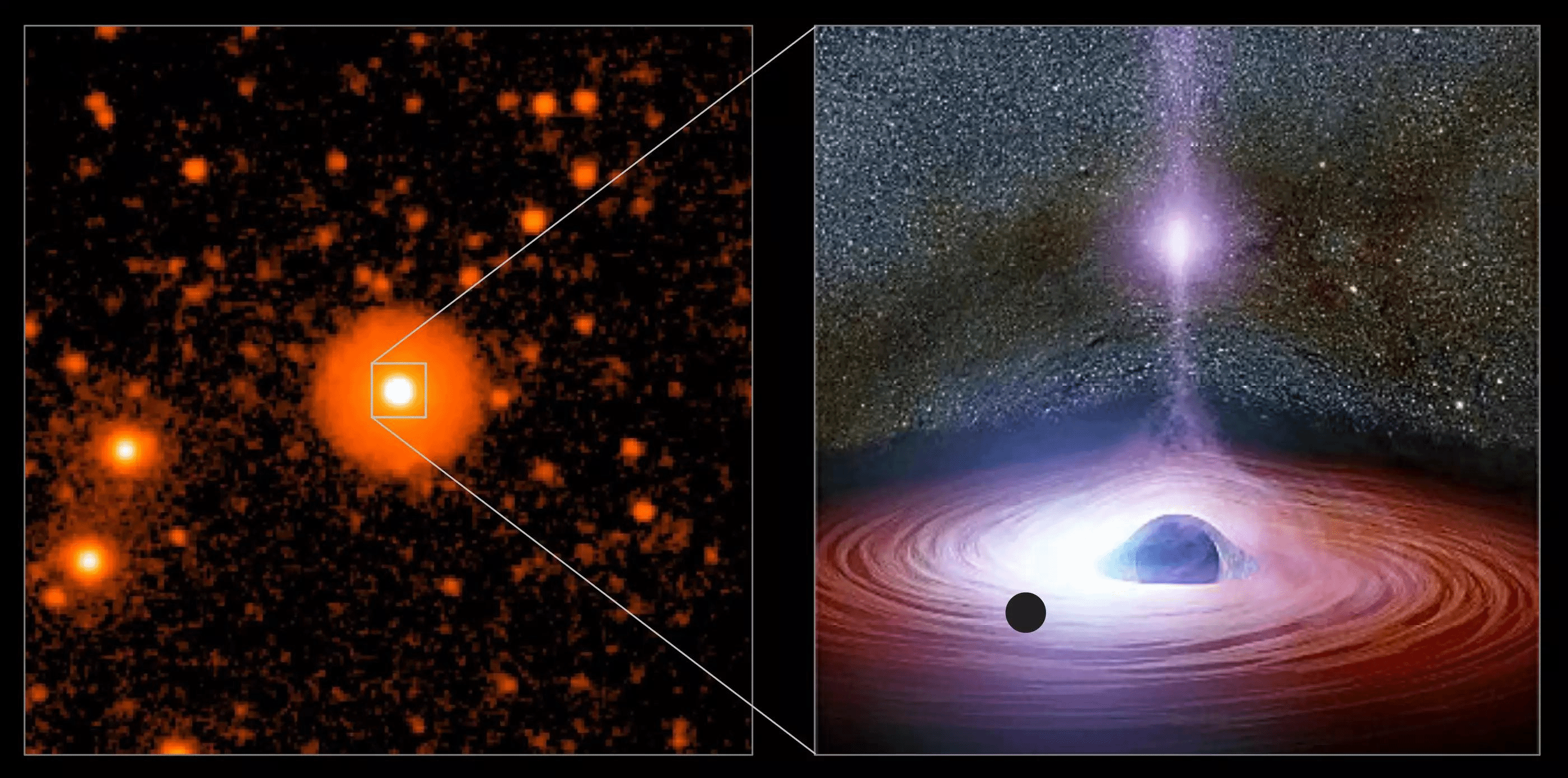

Fig. 1: The left panel shows a deep ultraviolet image of OJ 287 and its environment taken with Swift.This is one of the deepest UV images of that part of the sky ever taken, combining 560 single exposures. The brightest source in the field is OJ 287. The black hole region itself cannot be resolved in the UV image. The right panel depicts an artist’s view of the very center of OJ 287, including the accretion disk, the jet, and a second black hole orbiting the primary black hole which has a mass of 100 million solar masses.

© S. Komossa et al.; NASA/JPL-Caltech

Blazars are galaxies that host powerful, long-lived jets of relativistic particles that are launched in the immediate vicinity of their central supermassive black hole.

When two galaxies collide and merge, supermassive binary black holes are formed. These binaries are of great interest because they play a key role in the evolution of galaxies and the growth of supermassive black holes. Furthermore, coalescing binaries are the universe’s loudest sources of gravitational waves. The future ESA cornerstone mission LISA (Laser Interferometer Space Antenna) aims to directly detect such waves in the gravitational wave spectrum. The search for supermassive binary black hole systems is currently in full swing.

OJ 287 is a bright blazar in the direction of the constellation Cancer at a distance of about 5 billion light years. It is one of the best candidates for hosting a compact binary supermassive black hole. Exceptional outbursts of radiation which repeat every 11 to 12 years are OJ 287’s claim to fame. Some of these are so bright, that OJ 287 temporarily becomes the brightest source of its type in the sky. Its repeating outbursts are so remarkable, that several different binary models have been proposed and discussed in the literature to explain them.

As the second black hole in the system orbits the other more massive black hole it imposes semi-periodic signals on the light output of the system by affecting either the jet or the accretion disk of the more massive black hole.

However, until now there has been no direct independent determination of the black hole mass, and none of the models could be critically tested in systematic observing campaigns, because these campaigns lacked a broad-band coverage involving radiation of many different frequencies. For the first time, multiple simultaneous X-ray, UV and radio observations, along with optical and gamma-ray bands were now used. The new findings were made possible by the MOMO project (“Multiwavelength Observations and Modelling of OJ 287”), which is one of the densest and longest-lasting multi-frequency monitoring projects of any blazar involving X-rays, and the densest ever of OJ 287.

"OJ 287 is an excellent laboratory for studying the physical processes that reign in one of the most extreme astrophysical environments: disks and jets of matter in the immediate vicinity of one or two supermassive black holes”, says Stefanie Komossa from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR), the first author of the two studies presented here. “Therefore, we initiated the project MOMO. It consists of high-cadence observations of OJ 287 at more than 14 frequencies from the radio to the high energy regime lasting for years, plus dedicated follow-ups at multiple ground- and space-based facilities when the blazar is found at exceptional states.”

“Thousands of data sets have already been taken and analyzed. This makes OJ 287 stand out as one of the best-monitored blazars ever in the UV-X-ray-radio regime”, adds co-author Alex Kraus from the MPIfR. “The Effelsberg radio telescope and the space mission Swift play a central role in the project.”

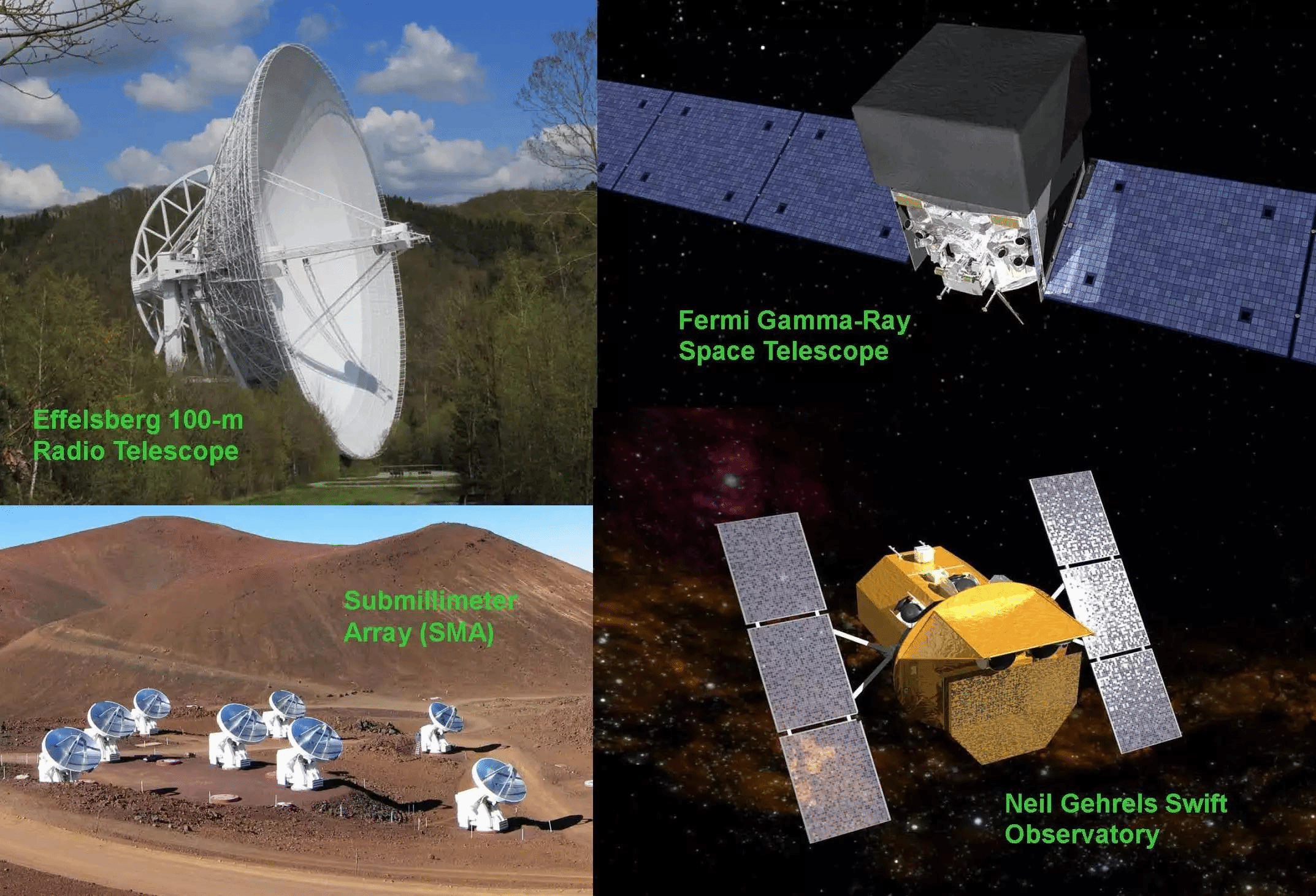

The Effelsberg telescope provides information at a broad range of radio frequencies, whereas the Neil Gehrels Swift observatory is used to obtain simultaneous UV, optical and X-ray data. High-energy gamma-ray data from the Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Observatory, as well as radio data from the Submillimeter Array (SMA) at Maunakea/Hawaii, have been added.

The jet dominates the electromagnetic emission of OJ 287 due to its blazar nature. The jet is so bright, that it outshines the radiation from the accretion disk (the radiation of matter falling into the black hole), making it hard to impossible to observe the emission from the accretion disk, as if we were looking directly into a car headlight. However, due to the large number of MOMO observations that densely covered the light output of OJ 287 (a new observation almost every other day with Swift), "deep fades" were discovered. These are times when the jet emission fades away rapidly, allowing the researchers to constrain the emission from the accretion disk. The results show that the disk of matter surrounding the black hole is at least a factor of 10 fainter than previously thought, with a luminosity estimated to be no more than 2 x 10^46 erg/s, corresponding to about 5 trillion times the luminosity of our sun (5 x 10^12 L_ʘ).

For the first time the mass of the primary black hole of OJ 287 was derived from the motion of gaseous matter bound to the black hole. The mass amounts to 100 million times the mass of our sun. “This result is very important, as the mass is a key parameter in the models that study the evolution of this binary system: How far are the black holes separated, how quickly will they merge, how strong is their gravitational wave signal?” comments Dirk Grupe of the Northern Kentucky University (USA), a co-author in both studies.

“The new results imply that an exceptionally large mass of the black hole of OJ 287, exceeding 10 billion solar masses, is no longer required; neither is a particularly luminous disk of matter accreting onto the black hole required”, adds Thomas Krichbaum from the MPIfR, a co-author of the ApJ paper. The results rather favor a binary model of more modest mass.

The study also resolves two old puzzles: the apparent absence of the latest of the bright outbursts which OJ 287 is famous for, and the emission mechanism behind the outbursts. The MOMO observations allow for the precise timing of the latest outburst. It did not occur in October 2022, as predicted by the “huge-mass” model, but rather in 2016-2017, which MOMO extensively covered. Furthermore, radio observations with the Effelsberg 100-m telescope reveal that these outbursts are non-thermal in nature, implying that jet processes are the power source of the outbursts.

The MOMO results affect ongoing and future search strategies for additional binary systems using major large observatories such as the Event Horizon Telescope and, in the future, the SKA Observatory. They could enable direct radio detection and spatial resolution of the binary sources in OJ 287 and similar systems, as well as the detection of gravitational waves from these systems in the future. OJ 287 will no longer serve as a target for pulsar-timing arrays due to the derived black hole mass of 100 million solar masses, but will be within the range of future space-based observatories (upon coalescence).

“Our results have strong implications for theoretical modeling of binary supermassive black hole systems and their evolution, for understanding the physics of accretion and ejection of matter in the vicinity of supermassive black holes, and for the electromagnetic identification of binary systems in general”, concludes Stefanie Komossa.

Fig. 2. The telescopes used for the observations include two radio telescopes, the Effelsberg 100-m dish in Germany and the Submillimeter Array in Hawaii, moreover two satellite observatories: Fermi in the gamma-ray range and the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory in the optical, UV and X-ray regime.

© NASA (Fermi & Swift satellite images), N. Junkes (Effelsberg), J. Weintroub (SMA).

The original Papers:

1. Absence of the predicted 2022 October outburst of OJ 287 and implications for binary SMBH scenarios, by S. Komossa et al., in: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters, February 23, 2023.

DOI: 10.1093/mnrasl/slad016

2. Multifrequency radio variability of the blazar OJ 287 from 2015–2022, absence of predicted 2021 precursor-flare activity, and a new binary interpretation of the 2016/2017 outburst, by S. Komossa et al., in: Astrophysical Journal, February 23, 2023.

DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/acaf71

3. Black hole mass and binary model for BL Lac object OJ 287, by Fukun Liu and Xue-Bing Wu, in Astronomy and Astrophysics: Letters, Vol.388, p.L48-L52 (June 2002)

DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20020566

A Parallel Press Releases can be found at

https://www.mpifr-bonn.mpg.de/pressreleases/2023/4